On Ancestral Skin and Bone

A version of this text was first published in McDougall, G. (ed.) 2023. The Prescription. Glasgow: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow.[1]

March 2020: Preambling in Suffolk

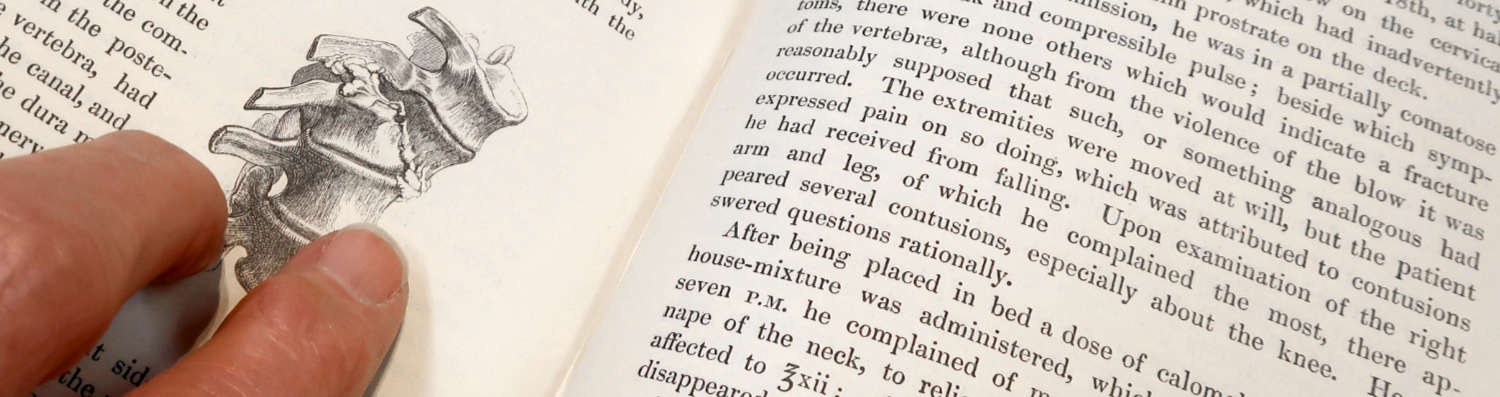

Let me start at a moment when the world has stopped, caught in the medical catastrophe of Covid. Confined, I resort to time-travelling, researching family history, diving into my riverine and sanguine lineages. London lightermen surface in succession through centuries: so many Williams, the sons and fathers of Williams who begat more Williams. Click, scroll, click – I strike genealogical gold: “Image from Astley Cooper’s Treatise on Dislocations and Fractures. Case CCCXLI.—William Billson, a lighterman, forty-nine.” Re-check the details, but nothing’s adrift. By chance I’ve found case-notes concerning my great-great-great-great-grandfather. The image – a gruesome drawing of a shattered and oozing spinal bone. Time passes: the world revolves once more.

April 13th, 2023: Library of Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow

Climbing a steep Glasgow hill, grand houses either side. Enter one. Ascend a wide, chandelier-lit staircase to the top-floor library. Admitted to an elevated archive. A hush. Astley Cooper’s Treatise lies waiting, supported on a pillow, as if sleeping. Half-afraid to wake it, pulses racing, I sit beneath the great blue and white cupola that gazes like a panoptical medical eye. Handling the Treatise carefully, slow-motion leafing, mindful of the old book’s crepitating spine, I read that Bransby Cooper, Astley’s nephew, dealt with my relative’s case. Fingertip touching the illustration, caressing: 187 years since the breakage. Now, reconnection, through an extraordinary visual vestige. Comprehending the Treatise as an optic for regarding others’ injury and pain. I photograph pages as a way of taking re-possession of my lost ancestor. For the records, staff photograph me photographing, their picture a family portrait equivalent.

November 18th, 1836, 2:30pm: London: Admission

Re-start the story, using Bransby’s words: “… brought to Guy's Hospital, having received a severe blow on the cervical vertebrae, from the hatch of a vessel, which had inadvertently been let fall on him, and threw him prostrate on the deck. Upon examination of the right arm and leg, there appeared several contusions […] He answered questions rationally. At seven P. M. he complained of much pain on pressure over the nape of the neck, to relieve which he was cupped”.

In retrospection: reconstructing the accident scene in my mind’s eye. Midday. Full tide. Evil new-moon weather, fierce wind, icy rain. The Thames choked with rolling, slippery-decked ships. Men working dangerously fast. William stooping, peering down into the swaying vessel’s deep hold. After that impact, free-falling through pitch-black space, feeling the lucky tattoos’ power – his sole insurance – expire. “Man down! Gangway!” Manhandled ship to shore: carted, semi-comatose, away.

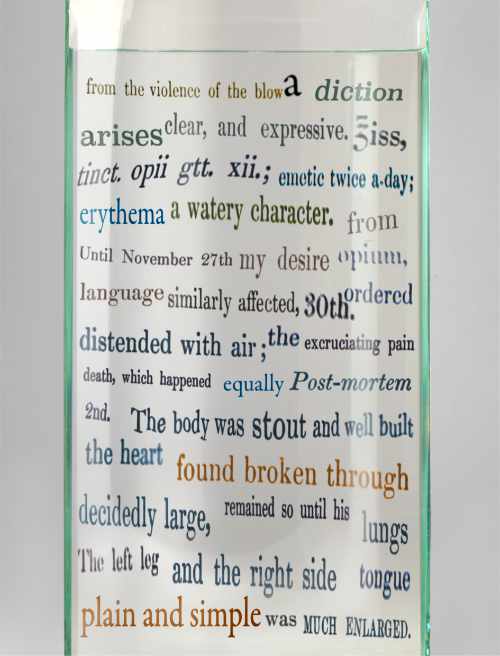

April 18th, 2023: Prescriptions

Bearing Astley’s pessimistic 1822 prognosis in mind – “I have scarcely known the subject of this injury to live beyond a week” – Bransby perseveres. For a fortnight he prescribes: ‘cure-all’ cupping, sedatives, emetics, diuretics, purgatives, fomentations, sinapisms, hypnotics, ever-stronger pain-relievers, opium, four ounces of brandy and one pint of porter daily. “Not comatose”, nor fully conscious, William submits to blood-letting, relentless dosing, plastering with irritant pastes: his body, the woebegone object of inquiry. Drugged, half-drunk, he responds to the influx with copious and effortful peeing, retching, and worse – blurting expulsions draining dignity to the dregs. William drifts, dreams, hallucinates. Missing the river, his Mrs. – precarious. Stone-heavy, sinking.

April 20th, 2023: Enlightened

Who are the Coopers? The archive’s spell sets me searching, excited, obsessed, flipped into hypergraphic note-making spin – books, laptop and printer spewing biographical details.

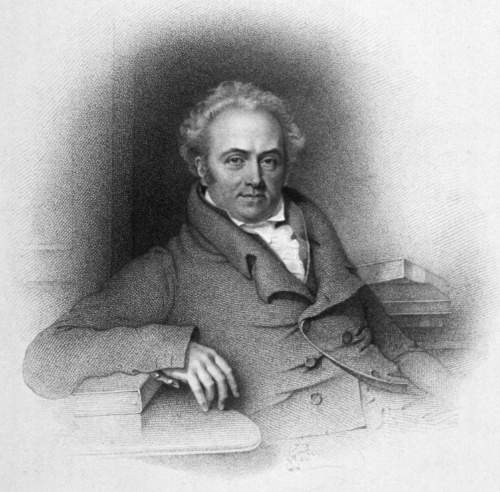

Stipple engraving by J. S. Agar, 1825, after A. Wivell.

Wellcome Collection. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Sir Astley Paston Cooper, Bart. F.R.S. Born 1768, Norfolk. A surgeon’s nephew. Tearaway and traveller. Learned from two stellar surgeons: Hunter and Cline. Expert on the ear, fractures, mammaries, hernia, cerebral circulation. Professor of Anatomy. Royal College of Surgeons, President. Unabashed vivisectionist, unflinching while inflicting human or animal pain. Showman. Charismatic medical celebrity. Excised a cyst from the royal crown. Baronetcy bestowed by King George, plus a fine table (not for dissecting). 1813 income, £21,000.00 (approx. £1,200,000 in 2023). 1841, died. Dissected, at own (pre-mortem) request, by colleagues.

Lithograph by J. Bizo

Wellcome Collection.

Bransby Blake Cooper, F.R.S. Born 1792, Norfolk. Nephew to Astley. Too seasick, homesick, for the navy. Medical studies in London: working as his famous uncle’s pupil and protégé. Broke off to treat battlefield wounded during the Peninsula wars. In Edinburgh, qualified as physician. President of Edinburgh’s Royal Medical Society. 1818, to London, assisting elderly Astley teaching dissection and anatomy to a class of 400. Anatomy Demonstrator. Described as “well made, muscular, a good oarsman and pugilist, and a good shot […] beloved of his pupils” [2]. Libelled by The Lancet after performing a fatal lithotomy: case won. Became Astley’s biographer (hagiographer, according to some). Editor of much enlarged version of the Treatise. 1853, died. Distinguished, but always eclipsed by Astley.

Careerists, but their compassion is evident, written between the lines. Rational men of science, respectable, yet readable as ‘dirty workers’ too – disparaged by some for touching matter that others categorically refused. Industrious, engaged in high-risk endeavour, they worked unprotected: no antibiotics, PPE, disinfectants: no superstitions or prophylactic charms.

April 30th, 2023: Atlas

Astley wrote, “From the vicinity of our hospitals to the river, sailors are often brought into them with injuries of the spine”, but other river-workers arrived too. In the Treatise’s cervical fractures section alone, these dock-labourers’ accidents: man crushed by 150 lb sack of malt; shipwright who fell 20 feet from a wharf; wagoner who fell when loading his vehicle; porter who fell while carrying a heavy load; youth who fell from an overturning wagon which then crushed him; man who fell from scaffolding; robust water-carrier hit by a cask. A compilation of collisions, falls, crushings, all fatal, each one commemorating some unregarded Atlas brought down, broken-necked, by unbearable overload. From the visual archive, instructive images, Boitard’s and Doré’s prints make the chaos and danger of frenetic dock-work explicit.

May 10th, 2023: Lighterers

“At command of our Superiors” – so says the lightermens’ motto, but who were these workers? Cargo shifters, ferrying goods between ships and docks, literally lightening the loads of vessels too deep-draughted to navigate shallow water. Puntmen and bargemen, their counterparts, worked the Clyde. All were expert oarsmen, rowing solo or paired: “a truculent bunch, notorious for their ‘immodest, obscene and lewd Expressions’” [3] – “the epitome of the tidal river […] wild, uncultivated, surly” [4] – their skills handed on, via apprenticeship, father to son. And who were these mens’ ‘Superiors’? London importers of tea, spices, furs, timber would claim they were. In Glasgow, tobacco lords and slavers, sugar, rum and cotton merchants would say likewise. Yet both cities’ boatmen acknowledged their governors as wind and tide: they obeyed the mutable elements, the movements of celestial bodies. Here lies the motto’s ambiguity – its crafty concealment of the river-mens’ obedience to nature’s authority alone.

May 11th, 2023: Curious

Unable to picture cupping, backtrack to Glasgow to consult RCPSG Heritage staff. They say that the technique, used for millennia, may either be ‘dry’ or involve blood-letting. Once believed to rebalance the body’s humours (blood, bile, phlegm) which ruled health and emotions, it drew out ‘bad matter’, relieved pain. Recently revived by sports therapists, as evidenced by tell-tale polka-dottings on Olympic athletes’ skin.

We examine the collection’s 1850 cupping set used by a Glasgow physician on his wealthier patients. Out of a velvet-lined box come stemless glass goblets (each clothed in a well tailored chamois-leather sleeve). Then, the tiny spirit-burner, and the scarifier – a brass cube with four slots on one face. Its alarming flick-knife action ejects twelve tiny razor-sharp blades. We leave the fragile items laid out, as if ready for the procedure to begin.

November 18th, 1836, 7 pm: Cupping

A commotion on the stairs. The door flies open. Followed by eager students, Bransby strides in. “Gentlemen! Hush! Let us begin.” William is raised, a student either side. One supports his head. Another bares his back. The burner is held to a cup. Bransby deftly applies the unsterilised scarifier to William’s skin. Demonstrating, he places the heated cup on William’s nape, explaining how heat creates a vacuum, making the cup cling leech-tight. Beneath the glass, flesh bulging, free-bleeding. The students try, applying more cups that leave scarlet contusions – William oblivious of his peculiar new stigmata.

June 22nd, 2023: Skin

Scratching and shedding peppery scabs. Ten days back, I blended mustard powder and water to a paste – step one of a DIY sinapism experiment. Applied a 50p sized dab to my wrist. Stuck on a plaster. Instant result, strong burning: 18 minutes later, enough of the cigarette-stubbing sensation. After rinsing, a raised puce blotch. Conclusion: first-hand experience of sinapism’s effects suggest that maybe the point was to divert patients’ attention from their original injury’s pain. Bransby prescribed poultices, embrocations and fomentations (made from herbs, clay, and salts) – the latter “warm [and] applied to the back” as a rash had “appeared […] extending towards the chest”. This he “attribute[s] to the scarifications” made during cupping. Working before germ theory’s advent, unaware of microbial complications, Bransby could not recognise that William’s “erythematous blush” was an inauspicious portent of infection.

June 26th, 2023: Specimens

At the Museum of Anatomy, grotesques, exquisites exposed, testament to industrial-scale dissection. The labels name names (Hunter, Phoca vitulina, Cleland) but, stonewalling, explain nothing. Superimposed on a horse’s eye, my own eye’s reflection, both merged in the glass pane. In coincidental self-surveillance, looking at my eye looking: seeing how reflections interact with flaws in the jars’ glass walls, how these generate unintended optical effects – warped contortions of putative physical ‘facts’.

June 27th, 2023: Bone

Contouring the sixth cervical bone’s features: arachnoid, dura, facet, foramen, ganglion, lamina, nucleus, pedicle, plexus. A small structure endowed with an impressive vocabulary by diligent anatomists. In my palm, something transcending the mundane ‘reality’ of a replica bone made “in unique unbreakable plastic”, bought online. This cast, a technologically-produced trace, is also a relic of someone, a donor whose embryonic spinal bones first budded at eight weeks. Bone’s underwater origin located in the Silurian corals, crinoids, that raised tentacular blooms on calcareous stalks. Bone’s forms unfinished, still evolving.

July 1st, 2023: Docklands

“To work on, or by, the river was in itself disreputable.”

Peter Ackroyd, Thames: Sacred River

Start walking, two centuries back, near Guy’s Hospital, following the Thames eastwards. Scores of triple-masted cargo ships, lightermens’ tiny boats bobbing amongst them. The father of Sir Thomas Guy himself, a Southwark lighterman. Past reeking tanneries in Bermondsey, Horsleydown, where side-streets descend to quays and treacherous, weed-tressed green stairs. Quickly bypass Whore’s Nest, Bull Alley, Dog and Bear Yard – places of brutal fates, the fates of brutes. Locating my 18th and 19th century ancestors’ addresses. Dickens’ infamous criminal haunt, Jacob’s Island, right on their doorstep. Here, putrid dead dogs twirl in pungent tidal ditches enclosing the ‘capital of cholera’. Dickens saw the wretched, waterlogged lives lived here: houses with “slime beneath; windows broken and patched […] rooms so filthy, so small […] dirt-besmeared walls and decaying foundations” [5]. A missionary defined the locals as watermen, labourers – “of the lowest class [corrupting] one another [in] a thriving nursery for immorality […] drunkenness a predominant vice”[6].

Begin again. Afoot in Glasgow’s industrial docklands – to Saltmarket, Bridgegate, Gallowgate – the mirror-image of London’s riverside: worse in places. Cargo ships queue four-deep off Broomielaw. Factories, mills, foundries, shipyards, warehouses, rashed across Clydeside panoramas. As in London, poverty and ostentatious wealth co-existing. In 1844, appalled by reports of conditions in the Glasgow wynds, Engels was incredulous that in “any civilised country, so large an amount of filth, crime, misery and disease” could exist. He saw rooms where up to “twenty persons […] sleep promiscuously on the floor”. Who were they? The same “lowest class” labourers that the London missionary saw. Disreputable? Maybe. But the epithet adds stigmatising insult to the injury of expendable workers. What a journey: every step of it walked on my desk, finger-tiptoeing over pictures and maps.

July 19th, 2023: Conduits

The archive discloses rivers and docklands as conduits, delivering not only goods but also the human by-products of capitalist machination, commercial ambition and exploitative greed – a never-ending flow of casualties and corpses carried to anatomists’ enquiring hands, eyes, and minds. Bodily dismantling, prerequisite for building the body of medical knowledge.

December 2nd, 1836. 2:00am: Observations

With William “complaining of excruciating pain”, a final sinapism was applied. At 4 a.m., under a waning crescent moon, and on a falling tide, he died. In a post-mortem micro-portrait, one last glimpse of him given: “stout and well built, but not very fat, the heart decidedly large” – the unwitting ambiguity of that last phrase, so poignant. Other observations: opaque thickening on the anterior coronary artery, kidneys enlarged and cystiform, left leg full and tense, inflamed, and tumid. Time and again, hitting the wall of arcane medical words. Scrutinised by a 21st century surgeon, the notes yield different diagnoses – the possibilty of heart failure, pulmonary embolism, an infected leg (gangrene/cellulitis?), deep vein thrombosis, upper limb weakness, prospective paralysis. Bransby cites the cause of death as “erysipelas” (skin infection) and, inexplicably, secretes this verdict, printed in near-microscopic text, in the Treatise’s illustrations list. Why?

A medical success? For whom? William survived for 14 days, double the time Astley predicted, thanks perhaps to medical advances made between the Treatise’s first 1822 edition and William’s 1836 case. Or was it that William was tough, headstrong, desperately striving to survive, his effort rewarded by doubling the days he suffered? Questions begetting ever more questions.

July 23rd, 2023: Iterations

“Figures are ephemeral, and the smallest movement scatters them to produce others.”

Arlette Farge, The Allure of the Archives [7]

Scissoring the outlines of a print-out of the broken bone illustration, my replica vertebrae to hand. Something’s amiss: a discrepancy between drawing and replica. The illustrator has the bones’ proportions wrong, too tall, cervical and thoracic shapes seemingly muddled. Artistic licence, or error? Did he work direct from the specimen, or from verbal description, or hastily scribbled instructions? More questions, confusions, doubts. Despite all Bransby’s assiduity, his “desire to be perspicuous”, his assertion that the illustrations are “correct, clear, and expressive”, the truth of this bone is, ultimately, fugitive. What am I left with? Only the refractory scatterings of representation, reproduction, re-presentation. Through the drawing and those delusive deformations held in the anatomy museum display, truth’s ephemerality and plurality are revealed – not a clear-cut case.

How to stop, step back, from a story with so many starts? Close the book. Finish by pointing to how the story led, and still leads, to different destinations and as yet un-concluded ends: William’s body to the dissection table, thence to the paupers’ burial ground; his widow, Ann, to Bermondsey workhouse; their genes still descending; me – to Glasgow. How I wish that my great-great-great-great-grandparents, both the Coopers, my dad, could see me here, writing this. Now.

Image: © Kim Crowder & P.F.White 2025.

Showing St. Thomas's and Guys Hospitals, The Borough, Tooly Street.

Public domain.

Image: © Kim Crowder & P.F.White 2025.

“[The archive] stops us in our tracks and provokes reflection […] there is no such thing as a simple story or even a settled story.”

Arlette Farge, Ibid. pp. 27, 94.

Encountering the wonderful RCPSG archive certainly stopped me in my tracks! That said, the writing of my essay proceeded via a tension between movement and stasis, requiring alternations between sitting at my desk, or the library table, and travelling physically, electronically and imaginatively. Farge’s idea that the “simple story” does not exist has been a productive one to work with: it allowed me to let my writing go ‘all over the place’, to use multi-perspectival versions.

Choosing to work from the account of a relative’s predicament contained in a textbook long used in medical training, in Britain and beyond, presented certain challenges. Given that regarding the pain of others is inherently problematic (Sontag, 2003), how could I temper sometimes playful inventiveness with due respect for my relative and his living descendants, as well as for the Coopers, and this project’s host? How could I make fragments selected from Cooper’s case-notes relate to the enormous and interlocking contexts of medical advance, imperialist expansion and trade, industrialisation, and their impacts on the bodies and conditions of labourers in Georgian Glasgow and London? Which literary device could bring these elements into articulation?

Reading surgeons’ casebooks held by the RCPSG prompted my decision to produce a disjointed essay shaped as an episodically disorderly diary. Adopting the diary’s textual economy – the discursive immediacy of its declamatory short clauses and lists – enabled me to generate the energy and pace for covering distance. It allowed for agility, expansions, and compressions while sequencing the essay’s themes. The form offered liberty to speak creatively both with and to the disciplined, and sometimes bewilderingly formidable, medical archive. It also granted permission to confess to, and work with, doubts and confusions.

Perhaps the archive and ‘the story’, alike, are unsettled. Writing this essay involved much more than cerebral circulation: in researching I’ve been grabbed by an impulse, a compulsion, verging on feral, that has fired unanticipated synaptic leaps. The refractoriness of words, ‘facts’, and forms that refuse supposed limits and boundaries has intrigued me. There lies the attraction, or as Farge has it, the “allure”, of intercoursing with the archive: through this, its complicated contents and inhabitants may be constantly revivified, kept moving.

My thanks to Professor Ian Bone for helpful medical insights; P.F. White for photography and image production; the late Ronald Blythe for his erstwhile encouragement.

Kim Crowder, 2023.

Notes and References

-

McDougall, G. (ed.) 2023. The Prescription: Creative writing inspired by the archive. Glasgow: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. It may be possible to obtain a copy of this publicaton from Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, 232 - 242 St Vincent Street, Glasgow, G2 5RJ. +44 (0) 141 221 6072

[Back] -

Quoted in Burch, D. 2008. Digging up the Dead: The Life and Times of Astley Cooper, an Extraordinary Surgeon. London: Vintage Books, p.253.

[Back] -

Quoted in White, J. 2012. London in the Eighteenth Century: A Great and Monstrous Thing. London: The Bodley Head, p.222.

[Back] -

Ackroyd, P. 2008. Thames: Sacred River. London: Vintage Books, p.253.

[Back] -

Quoted from Charles Dickens. Oliver Twist. 1838.

[Back] -

Quoted in Walford, E. 1878. Bermondsey: Tooley Street. https://www.british.history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol6 Accessed 21/6/2023.

[Back] -

Farge, A. 2013. The Allure of the Archives. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, p. 94.

[Back]

Read more by Kim Crowder:

Unless otherwise acknowledged, all material is © Kim Crowder and may not be reproduced or copied in any form without written consent.

Site by Allpicture.