Extracts from a Nature Diary

This diary, begun in 2016, offers a way of preserving and sharing experiences of nature in an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

The diary tracks observations of notable weather events as well as recording the ordinary and extraordinary signs of seasonal and environmental change as they occur in the fields, woods, heaths and marshlands close to my home. In tying together dates, places and occurrences the diary also documents the comings and goings, appearances and disappearances of particular plants, birds, insects and animals who frequent the area. Many of the entries are written against the backdrop of the processes and effects of the intensive agriculture which is practiced here.

This initial selection is drawn from entries focusing on summer events and encounters in East Anglia, where I lived for many years before moving to Scotland in 2021.

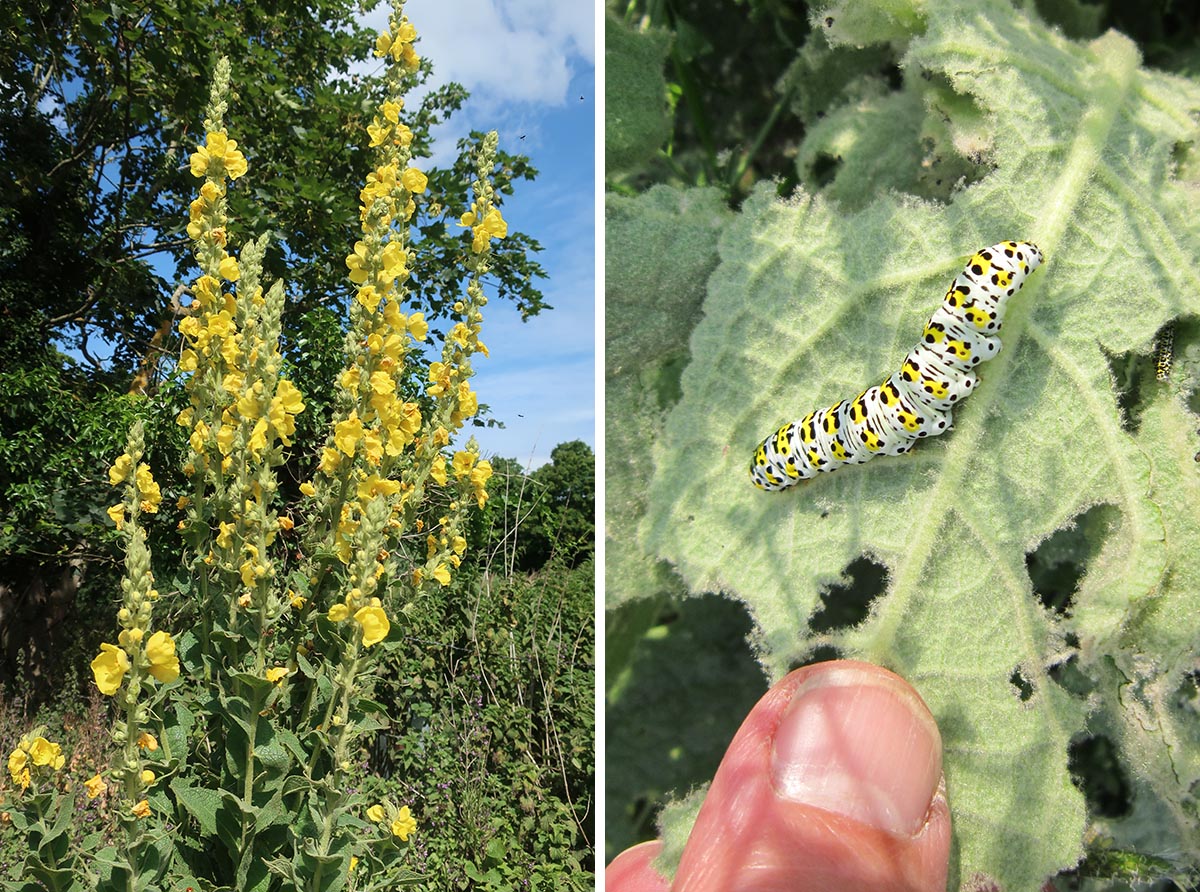

4th June 2019: Mullein Moth Caterpillars

Peter spotted a hatch of spectacular caterpillars in the paddock today. Each year he carefully avoids cutting down the half dozen or so mullein plants that grow there as we like to see the plants’ tall pyramidal forms, their plushy silver-green leaves and their tall spikes of yellow flowers. This is the first time that we have seen the plants host a caterpillar hatch.

The biggest of the caterpillars were more than five centimetres long, their flashy colour scheme consisting of a limey-cream background striped with bold transverse yellow bands each crisply spotted with black. I thought at first that they might be one of the varieties of hawk moth caterpillars, but after much picture searching I concluded that they are definitely Mullein Moth caterpillars. There was an obvious clue to their identity in the name of the host plant!

When I looked up Mullein Moth facts online I learned that the adult's wingspan measures almost five centimetres. The moth flies at night and feeds on flowers. Its eggs take ten days to hatch. Knowing this, I looked back ten days in my journal to the night when we last went out to hear the nightingale, May 27th. Sitting staring out of the window at dusk that night, killing time before the nightingale sang, I saw a huge moth settle on the window pane, its deckle-edged wings fully extended and its huge eyes shining. Following today’s moth research, I now know that this was a Mullein Moth.

The moth belongs to a huge classificatory group, the Noctuidae, otherwise known as owlet moths. Compared to the caterpillar, the adult is dowdy, its wing patterns shaded in subtle creams and browns, similar to barn owl colours. But the moth’s most distinctive features are, firstly, the intricate scalloping of the wing edges, and secondly, the tufted projection on its crown resembling a punky mohican hairdo. At rest, with its wings folded, the moth looks very like a velvety flake of bark. Knowing all this, It's tempting to see it as a strange hybrid, part-twiggy, part-owly, part-punky.

We found several more of the caterpillars, much smaller ones, distributed amongst the well-chewed leaves of three of the mullein plants. It takes up to thirty days of mullein‑fuelled feeding for the caterpillars to reach full size. Then, entering the next somewhat strange stage of their life-cycle, they desert the ravaged mulleins and burrow underground to pupate inside a tough cocoon for up to five years. I like the idea that ever since we began using the paddock five years ago, the moths who recently laid the eggs which produced these amazing caterpillars have been secretly developing right under our feet. Although the voracious caterpillars are capable of completely stripping the mullein’s foliage, we won’t be disturbing them, because somehow the plants still manage to flower and re-seed themselves year after year.

22nd June 2019: Thick Legged Flower Beetle

As the temperature was rising fast, I walked the dog early before it was too hot. We took a leisurely saunter, following a path whose verges were thick with newly opened poppies, not just the little vermilion field poppies, but the opium variety too, the ones whose blooms are the size of tea cups. Their glossy petals shone in the sunlight in many rich shades of pink, purple and magenta. Looking closely at several of these I saw that each flower cup sheltered a beautiful tiny beetle. Seen from one angle the beetles looked almost black, but from another their iridescent wing cases sparkled with a deep metallic turquoise shot with blue and indigo.

These were Thick-legged Flower Beetles, Oedemera nobilis. The descriptive name comes from the males’ tactic of attracting females by showing off their big shapely thighs. After looking at magnified images of them, it was hard to resist the idea that the beetles followed strict body-building routines to achieve immense, pumped up, high-gloss 'glutes'. How could any amorously inclined lady beetle not be tempted by the hologram flashings of such magnificently toned limbs? Perhaps, as they displayed themselves, the male beetles called to one another from poppy to poppy: the one on the pale pink flower boasting, “Look at me! Pink is the perfect posing colour!” only to be challenged by another retorting, “No! I prefer purple. Pink makes me look off colour, completely jaded!”

23rd June 2019: Jackdaw Fledgeling

I saw a sad sight on the gatehouse drive while walking the dog. A young jackdaw was hopping along the path, just managing to keep about twenty feet ahead of me, but no matter how hard he hopped and flapped he couldn’t take off. His left wing drooped and skimmed the ground, so his plight seemed due to injury rather than inexperience. His parents were close by, up in the sycamores, calling, encouraging him into the air. Still hopping quickly and determinedly, the juvenile left the path and moved into the cover of the long grass. There he was sheltered, but it was far harder for him to move as his injured wing kept snagging amongst the stems.

We did our circuit down the drive, up the hill, and back along the drive and as we approached the place in the long grass, two adult jackdaws rose hurriedly into the air. Their fledgeling was still there, still struggling. I looked at him, weighing up the pros and cons of what to do. If I picked him up, what would I do to help? Should I, could I, kill him there and then? If left alone, might he recover? Should nature be allowed to take its course? Harriers and sparrowhawks are never far away. The parent birds flew overhead, twin black silhouettes crossing and re-crossing the blue expanse of sky. The dark shadows of the pair passed one after the other over the ground, and then over their injured chick like two slow and compassionate caresses. I walked on, hoping that the end to this would be swift - and soon.

12th July 2018: A Gift of a Damselfly

Many butterflies on the wing: cabbage whites, ringlets, peacocks, tortoiseshells and red admirals. It’s peak time for summer’s most delicate and beautiful fliers. Today a friend wordlessly handed me a little box which contained the tissue-wrapped corpse of a damselfly. It was one of the exquisite but short lived purple-winged ones we look forward to seeing each summer when they fly for a few days above the stream in her meadow - a Beautiful Demoiselle (Calopteryx virgo). What a gift! As death was already fading her colours I could hardly wait to look at the damselfly under the microscope.

Magnification revealed how the wing’s transparent membrane was stretched tight between minute veiny structures that resembled tiny ladders. The side-rails and rungs of every one were studded with brilliantly iridescent light-emitting cells whose flashing greens, golds, and turquoises reminded me of the tiniest imaginable strings of LED fairy lights. Gleaming metallics sheathed the demoiselle’s body, her thorax and tail armoured in foils of intense turquoise-blue. She was a truly fabulous creature. Part of me knew that she ought to be returned to the place she had come from: the stream water in which she had been made should also unmake her, and yet, another part of me knew that I could not let the marvel of her go.

7th May 2018: Grass Snake (Natrix helvetica)

Heatwave weather, the temperature close to eighty degrees. On the gravelled farm driveway, right where the tractors turn in, I found a small grass snake. It was no bigger than a brand new pencil. Assuming that it was dead, I picked it up. Disliking the prospect of it being crushed, I wanted to hide the snake amongst the undergrowth. But first, as it lay slack in my sweating palm, I took the chance to admire its pale lemon-yellow collar and beautiful olive-grey coloured scales close-up.

I blinked. Was I imagining it, or was a hairline crack of black showing between the snake’s lips ? I watched more closely and the jaws gradually opened wider, a fraction of a millimetre at a time. A faint tremor registered on the flesh of my palm: the snake was clinging to life by a thread. It must have become over-heated, disorientated and exhausted as it had helplessly twisted one way and another trying to escape the baking gravel.

Hoping to further revive it, I took the snake indoors and put it in a big glass dish to which I added a few handfuls of fresh grass sprinkled with water. The snake lay inert and unmoving on the grass, jaws agape. After putting a lid on the dish I left it in the cool pantry for a while. Twenty minutes later the snake had arranged itself into a neat coil and when I took the lid off the dish it looked up at me, alert, flicking out its tiny black tongue. I left it again, another quarter of an hour, hoping that it would by then have cooled right down and maybe sipped some of the water.

The next time I touched the dish, the snake instantly responded by unwinding its coils, zig-zagging and lashing wildly about. The moment the lid was lifted, the snake was out of the dish and out of control wriggling along the windowsill tiles whose smooth surface was ideal for high speed slithering. There had been a miraculous recovery. Every time I got my hand over it, the snake literally slipped through my fingers, time and again darting right, then left, then rearing up against the window pane. Wary of making a clumsy grab and causing injury, I summoned help from Peter. His tactic was to first block the snake’s progress with the dish lid, then use it to deftly flick the snake gently off the windowsill and back into the grass-cushioned dish.

The snake was obviously ready to return to the wild, so we took it in the securely lidded dish to the bottom of the garden, well away from mowers or sharp-eyed predatory birds. As I took one last, long look, the snake reared up, fixing me with a baleful stare. If the scales were reversed and he was my size and I was his, that stare would have made me run for my life. After counting down “three, two, one”, I whisked the lid aside and the snake was up and over the side of the glass, streaking back into its own element - grass.

12th May 2019: Bee Rescue

Mid morning we went for a bike ride. After speeding down the hill I slowed as the road surface was dangerously littered with a scatter of newly fallen debris beside the big oak tree. A huge branch lying at the roadside had either collapsed under its own weight or been torn off by a big vehicle. We remembered hearing a sound like a thunderclap earlier on and now we knew that this must have been the sound of the massive branch breaking. My first reaction was regret that such an old tree had been so badly injured.

When we got off our bikes to look more closely at the damage I noticed hundreds of bees swirling in the air. Amongst the wreckage of the branch I saw the focus of the bees’ attention - their ruined nest all smashed in pieces on the ground. It must have been inside the branch that had broken. A few days back we had noticed the bees going in and out of a small hole in the branch. Cautiously I stepped close enough to see that some of the bees were pale and some were dark. The pale ones were paying great attention to the biggest slabs of fresh cream-coloured comb that were strewn across the verge, while the dark ones were agitatedly moving about a much smaller fragment of older looking comb.

The bees were in need of help, so I hurried home and found some beekeepers’ contact numbers. The first man I called turned out to be too far away in Norfolk, but then I found another based just down the road in Hollesley. This man promised to come, although he warned that he didn’t think he could do much. He said that if the damage had occurred when the bees were naturally ready to swarm, then they’d just swarm and head off with a new queen to find a fresh place to nest. But as they weren’t ready to swarm, they’d be in a state of angry confusion and probably dangerous to handle. I thanked him and got on with the day.

Late afternoon I re-visited the bees and found that a notice had been tacked to an adjacent tree. It read ‘Caution. Bees working in the area. Beekeeper will return later’. Every scrap of broken comb had been cleared away and a small wooden bee box left in their place. A steady stream of bees was passing in and out of the box, behaving much more calmly than earlier. The beekeeper’s plan was to wait for the bees to settle for the night, then come and take them.

Walking back up the hill I realised that the beekeeper who had visited could well have been the one I called, but equally it could have been a different one called by someone else who had also seen the bees’ predicament. This uncertainty seemed to fit well with the way that bees work collectively, different individuals communicating and labouring to one single end - the survival of the swarm. I’d checked the internet, phoned a man who told me to email him all the details and then phone another man. I’d then phoned the other man who agreed to travel to help. So my bee information moved back and forth across two counties summoning human aid from one skilled man for thousands of endangered insects. It’s possible that some other concerned passer-by had replicated all my actions and the beekeeper summoned by this person had arrived at the scene first. However it happened, information-sharing between humans had activated the assistance the bees needed.

Perhaps the bees, if they knew, would have approved of the sequence of co-operative behaviours that had taken place on their behalf. There was no flying or dancing for the humans involved, but there was some finger-tapping on keys, some vibrating of air on vocal chords, and a great deal of technological assistance delivered via phones, computers and satellites connected to a huge network of electronic communication systems.

It’s almost dark now, so hopefully after their eventful day the bees are settled and secure. They have so many air miles to cover tomorrow, so many flowers to visit.

25th May 2019: Robin

Over the last three evenings I have been watching a male robin who appears at 6.55 prompt and perches on the fence-post closest to the window. It’s definitely the same one every time because he is unusually large and has a very distinctive facial expression. His eyes are set rather wide apart and there’s an owlish intensity in his stare.

The first time I watched him I was bemused by his behaviour. He sat on the fence-post, an enormous grub clasped in his beak. Every few moments he would determinedly fly straight at the sheer face of the dense hedge. Each time, after seeming to collide with the hedge, he would settle once again on his post, the grub still firmly clenched in place, cocking his head from side to side and contemplating. As he repeatedly flew at the hedge, bounced off and returned to the post, I assumed that he was trying to penetrate the thick growth so that he could get in and feed the grub to fledgelings concealed in a nest deep amongst the branches. After watching his repeated collisions I began to suspect him of being not very intelligent as he appeared to be unable to work out how to gain access to his nest.

I pointed out the robin to Peter and together we watched the bird going through the same rigmarole of diving at the hedge, hitting it, then veering away. After several impacts, the robin perched on the post giving us a clearer than usual profile view of his head. We could see a small insect protruding from one side of his beak. Then when he flew, crashed the hedge and perched again there was another, and at the next flight, another. Far from being unintelligent, this robin was in fact an expert hunter. It was me who was being unintelligent in not recognising his amazing capability. Every single time he flew, he unfailingly picked a tiny insect out of the hedge. With his beak crammed with the maximum number he could manage, he shot off at top speed over the top of the hedge in a hurry to deliver his catch. He was here again just now, accurate, systematic and totally methodical, catching fly after fly. The robin’s hedge hunting expedition lasts about ten minutes each evening - and then he’s gone.

5th and 6th July 2020: Gravid Grass Snake Fatality

Walking in the lane, we came across a sad and terrible sight - a huge female grass snake run over, her flattened eggs, the size and shape of honesty seed pods, lay scattered in the blood pooled around her. If disentangled, the wreckage of her body might easily have been a yard long. At this size she could have been ten or more years old. She lay within inches of the verge and the safety of the thick undergrowth. Had her crossing begun just a fraction of a second earlier, she might now have been swimming in the pond in Water Wood.

This is not the first time I’ve seen such a sight. The collision could have been an accident, but there are people in the district who refuse to believe that grass snakes are harmless and will deliberately run over any that cross their car’s path.

Next morning, at the scene of this catastrophe, every shred of the snake’s body and all her ruined eggs had gone. The only trace of her was a dark bloodstain on the tarmac. The buzzards had taken her for a sky burial.