Thinking well ahead I book a routine vet visit for my geriatric rescue pony’s annual vaccinations and hormone-monitoring test.

The vet’s surgery calls to let me know that in line with newly introduced Covid-19 pandemic protocols, all non-emergency equine visits are cancelled.

Boris Johnson announces unprecedented quarantine measures. We are instructed to stay at home, no longer permitted to mingle with others. There are new police powers to enforce the instructions.

The weather turns unexpectedly sunny and warm - a change that lifts the spirits as we go into quarantine free-fall. But within hours the pony looks unwell, overheating in his super-shaggy winter coat. The spring grass is growing fast, suddenly flushed with nutrients which are far too rich for his system. Despite my careful restriction of his grass intake, spring is always a tricky time. If he was human, he would amply qualify for the current ‘at risk’ category. He’s 34, which equates to 100-plus in human years and he has two underlying and incurable health issues - laminitis, established during a phase of severe neglect he suffered in early life, many previous owners ago, and Cushing’s disease, a progressive and age-related hormonal imbalance caused by a malfunctioning pituitary gland. Usually both conditions are manageable following twice yearly vet assessments, but this year is different. Without testing, I don’t know how much the Cushing’s has progressed. I can neither stable him 24/7, nor stop the grass growing. He’s not an emergency. Not yet. But he is unusually slow and reluctant when I attempt to lead him out for his daily walks.

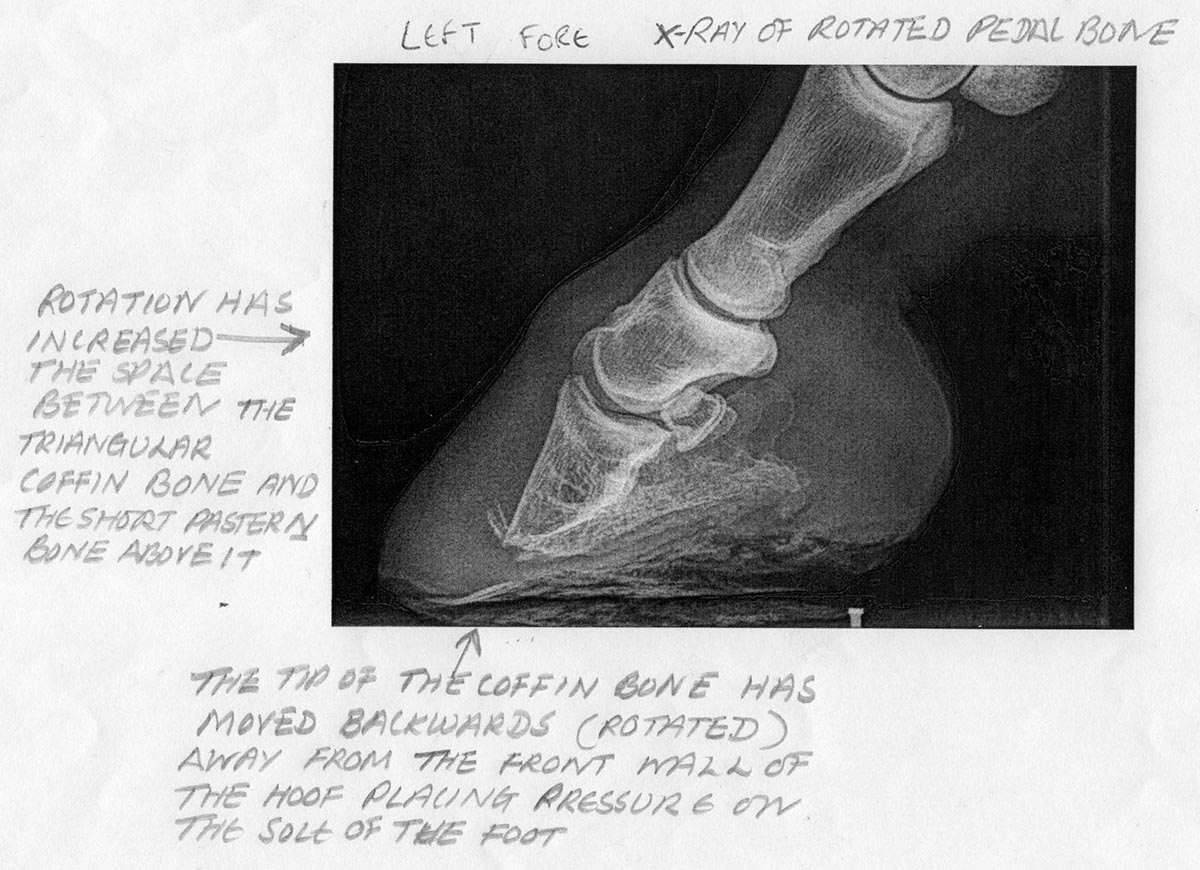

Laminitis and Cushings, are inter-linked. To understand a laminitis flare-up, imagine a tight-fitting thimble jammed onto a finger which a hornet then stings. As the venom-filled finger swells, the immovable thimble grips it ever tighter generating agonising heat and pressure. This is what rich grass does to laminitic hooves: constricted by the rigid hoof-wall, the foot’s inflamed internal tissues can’t expand. The pressure can be so intense that the pedal bone (colloquially known as the coffin bone) becomes permanently displaced, or, in veterinary parlance, ‘rotated’.

One of Cushing’s effects is excessive production of the stress hormone, cortisol. As well as playing a part in inducing laminitis, Cushing’s also causes increased hair growth and an inability to moult. So a vicious cycle ensues - in warm weather the thick, un-shed winter coat causes overheating which exacerbates the stress caused by the hormone imbalance. The laminitis-induced foot pain causes more stress, more overheating - and so the cycle goes painfully round and round.

Knowing this, I immediately decide to increase the pony’s usual anti-inflammatory medication dosage. I also re-position the electric fencing so as to reduce the size of the grazing area, but this is beset with potential problems. Even though he isn’t well enough for his daily walk, he still needs to get out and stretch his legs and to satisfy his grazing instinct, but if I make the grazing patch too small he will strip it it bare and begin to ingest sandy earth - a sure recipe for colic, and then he would certainly be an emergency case.

Every news bulletin reiterates the mantra ‘stay home, stay safe’. The rule has a second resonance in our household, as it now applies, albeit for different reasons, to the pony too. Here we are in pandemic lockdown with a locked down pony whose problem means that we must leave the house several times daily to care for him.

It’s unusually warm for March and the pony is already sweaty and dejected when I go to him first thing. Worryingly, he is failing to eat up all his food. In an urgent phone-consult the vet advises calming his system with a further increase to the anti-inflammatory medication dosage, stabling him for even longer periods each day, and, most importantly, clipping off his coat. A dilemma: I rely on a friend for clipping, but now social distancing is mandatory. When I remind the vet that the pony already has one rotated pedal bone, she unhesitatingly urges “Clip! It’s a welfare issue.”

I hesitate, consider. What to do? I want to act responsibly and follow the quarantine rules, yet I’m deeply indebted to the pony for the five years of companionship and pleasure he has given me. He deserves all the good care and quality of life I can manage as redress for the neglect that others subjected him to long before he found his way to his last owner and then me.

I call my friend Lucy. She’s eager to help, but first we discuss pandemic pros and cons at length. Will we pose unreasonable risk to each other, to our families, by meeting? Lucy’s husband is a farming sector key-worker. We count backwards: neither of us have mingled socially for a fortnight. What if we don’t clip? If the pony crashes I might need the vet and the knacker-man. What if neither could attend? It’s too awful to contemplate. Reviewing last year’s X-ray images of the pony’s feet, I know that that coffin bone mustn’t move another millimetre. We resolve to clip.

The temperature continues to rise and the pony is unbearably hot. Lucy arrives. Technically we break the two-only rule: I steady the pony, Lucy slices off great slabs of woolly horse-hair, and my partner sweeps up the ever expanding carpet of dangerously skiddy clippings. We can maintain the prescribed two metres distance while Lucy works at the tail-end, but this becomes more difficult as she progresses towards me. We take frequent pauses to cool the clipper blades and to give the pony a break - and crucially - to repeatedly reinstate the requisite space between us. The process takes almost two hours, long enough to attract negative attention from passers-by. Their accusative looks say it all: “Selfish! Ignorant!” In case I’m challenged I mentally run through the justifications for what must look like a frivolous and very badly-timed equine hairdressing session.

In pre-pandemic times, clipping is simply routine, no big deal, but this spring it’s become a medicalised animal welfare issue, fraught with problematic moral and ethical considerations. As far as we know, we have no symptoms, but in this awkward position we are decidedly under the virus's influence. Paradoxically, we find ourselves apparently breaking the newly imposed social distancing rules intended to protect humans while simultaneously complying with legitimate veterinary instruction given on animal welfare grounds.

One of the side-effects of the planetary pandemic and quarantine conditions concerns awareness, in the shape of self-awareness and awareness of one another’s actions. I notice how the recent upsurge of altruistic community spirit is being paralleled by less openly acknowledged negative feelings. It seems we are all becoming more self-conscious, more consciously self-monitoring as well as being more alert to others’ overt or covert social surveillance of us. The crisis is double-edged: whilst it involves the control and containment of micro-organisms and sickness, it also entails the spread of criticism, suspicion, judgement and blame. We glance over our shoulders to see if we are watched while staying on the lookout for watchers and rule-breakers. Super-sensitised to the point of paranoia, we are both surveyors and surveyed. Now I see how disease and social unease go hand in glove.

So far, so good: the vet’s advice is working. The pony seems brighter, more responsive, more comfortable. He’s eating up his meals of hay. I check his hooves three times daily, and every time find them stone-cold.

While we are beginning to grow more used to living by the quarantine rules, and working hard at the pony’s health routine, I think about the interconnections between human- and horse-welfare during lockdown. These prompt many questions: What is right? For whom? Why? Which imperative trumps which? Whose word goes in unprecedented times of disease precaution? The multiplying tensions between permission and precaution, infection and infraction are troubling.

How long will this last? Like us, the pony is growing restless. He neither likes nor understands his confinement. In between eating his hay rations, he stands staring over the stable door, longingly surveying the tantalising expanse of lush grass that he is not allowed to set foot on. Like us, he can’t have access to the things he enjoys and normally takes for granted. Chopped apples and peppermint treats are off the menu - too dangerously sugary - and the sliced carrots that normally garnish his feeds are on very short ration now that supermarket delivery slots have become unobtainable. The meagre carrot stock available at the village shop means that I can’t buy for him there either

Fourteen days since clipping: nobody in my household or Lucy’s is showing any symptoms.

One of the pandemic’s powers is becoming more and more obvious, namely its ability to expose just how closely everything and everybody connect in a myriad of tenuous and direct, tangible and intangible ways. Until this I could never have anticipated exactly how protocols, pony hair, warm weather, watchfulness, coffin-bones, cortisol, Covid-19 and Cushings would collide. The pony's problem has been just one micro-effect amongst the millions that are emerging as each day of quarantine passes.

Today the British daily death toll of 980 has overtaken that of Spain and Italy. I count my blessings.

As for the pony? A turning point today. The weather has cooled. His system has settled and the sparkle is back in his eye. He’s improved enough to resume his job of showing the new young greyhound the way around on his walks, stepping out with us into the new and abnormal normal.