This autumn there are First World War Tommies everywhere. In streets, parks, gardens, churches and stations or out in the landscape these soldier-shaped silhouettes, acting as stand-ins for the dead, have waited in position for the Armistice centenary. In telling this story I take my cue from the title of the silhouette project, There But Not There. It’s a story that is less about the catastrophic magnitude of death and destruction and more about just one injured soldier, a survivor, who made it home alive only days before the Armistice in 1918. More exactly, it recalls a life lived with a limb that was there but not there.

Twelve days after his 18th birthday in 1917, my grandfather, William Pearson, enlisted at Stratford in the East Surrey Regiment. I have a photograph of him which shows the new recruit seated on a kitchen chair in what looks like a small back-yard. He looks straight into the lens, unsmiling, his expression introspective and slightly uncertain. Dressed in his newly issued uniform - cap, boots, and tunic - he looks every inch a soldier until you notice the school-boyish shorts that reveal his slim legs and bare knees. His oddly incomplete outfit accentuates the recruit's in-between status as half-man, half-boy.

William would have completed six months training before his first posting, around September 1917, to his regiment’s Depot in France. None of his letters home survive, but there is a fragile and tattered letter, marked On His Majesty’s Service, which was sent on October 29th, 1918 to my great-grandfather, John William Pearson, a few weeks after the end of the second Battle of Bapaume. Through late August and early September, John must have been following news of this battle and although it had ended, he must have opened the envelope with trembling fingers, in a state of absolute dread.

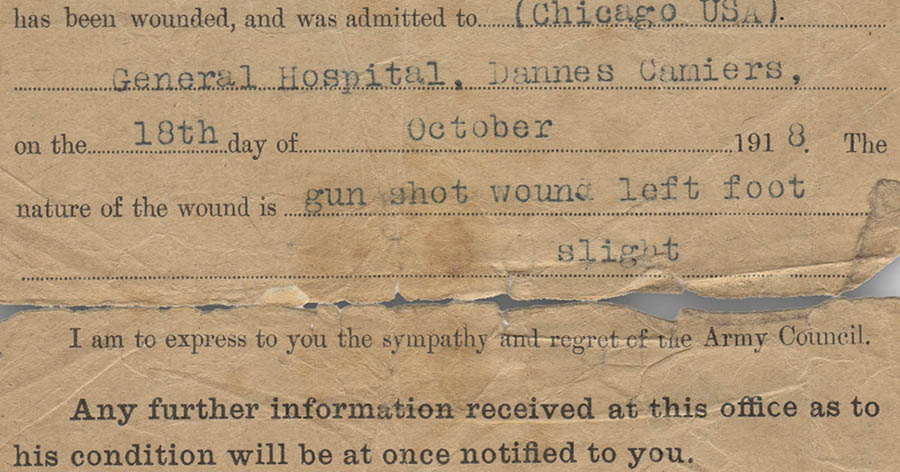

The first piece of information typed at the top of the pro-forma document is a code - E.S./Cas./-. In the calm of my office, a century later, I can see at once that this code clearly classifies my grandfather as a casualty. However, further down the page, the message opens with the ominous phrase, ‘I regret to inform you …’. I can imagine my great-grandfather drawing breath, his pulse racing, before he dared to read on, ‘… that a report has been received from the War Office to the effect that Private William Pearson, No. 35120 has been wounded and admitted to Chicago USA General Hospital, Dannes Camiers on the 18th day of October, 1918. The nature of the wound is gun shot wound left foot’.

What relief my great-grandfather must have felt as his gaze travelled the distance to the next word floating alone on a separate line like an afterthought - ‘slight’. Looking at the message this afternoon, I didn’t notice that word at first as it was obscured by the turned-back edge of a rip in the paper. What reassurance that single word must have carried back from France.

Another document takes the story a little further - William's army discharge certificate dated a year later, on 16.10.19. The phrase ‘Has served Overseas on Active Service’ is included in bold red type and the certificate explains that ‘He is discharged in consequence of being no longer fit for war service after serving two years and 158 days with the colours.’ His ‘Specialist Qualifications’ are described as ‘nil’, and the form confirms award of the British War Medal and the Victory Medal, plus one Wound Stripe. The form ends with a ‘description of the above named soldier when he left the Colours’. The details are as follows: ‘Year of birth 1899, Height five foot six inches, Complexion fresh, Eyes brown, Hair brown, Marks or scars - amputation of Left Leg.’ So what went wrong with the ‘slight’ gunshot wound?

My family history explains it like this. William was a Water-Carrier. On the day of his injury he was detailed to go to a pond, perhaps filling up cans, perhaps working with a horse-drawn bowser. While doing so, he was hit by a German sniper’s bullet. Injured, he collapsed in the water. With darkness falling, and continuing sniper fire, rescue was impossible, but somehow he survived blood-loss, shock and the chill October night. After 24 hours a padre reached him. I do not know if this man was British or French, soldier or civilian. Did he wade into the water thinking he was going to recover a teenage boy’s body, or administer last rites? Or did he actually know that the wounded soldier was still alive and desperate for help? What risk did he take in this rescue? William had more than his lucky stars to thank when he was transported to the American hospital and then shipped back to a Dover military hospital. But, here, in attempting to help another more badly injured patient, he fell, re-opening his wound. Gangrene developed in the foot and crept up into his lower leg, neither of which could be saved. Now an amputee, his radically extended convalescence continued at the Red Cross hospital at Walden Place, Saffron Walden and at Queen Mary’s Hospital, Roehampton where he received and learned to use what he called his ‘artificial leg’. He was one of the 40,000 British men who lost a limb in the war.

I keep the enlistment photograph of William as a fit, two-legged, teenaged soldier in a frame with the October 1919 discharge sheet confirming his disablement and unsuitability for further military service. Together the form and the photo bookend a phase of my grandfather’s life that he was reluctant to talk about. Perhaps he felt he didn’t need to say anything, thinking that his wooden leg, his all too obvious war-memento, said it all and was proof enough of where he had been, what he had seen and done. What sits unseen between the discharge form and the photo is William’s unspoken experience, a knowledge that thousands of his generation shared, one which a century on, has passed beyond living memory.

Since the 1980s I’ve been looking after my late grandparents’ suitcaseful of photographs and from time to time I’ve attempted to sort them into order. Some of the faces are easily identifiable, but there was always one studio photograph that I could make no sense of. The sitter, a slightly podgy, but very smartly dressed young man is posed with a cheeky looking little dog. For years I even doubted that he was a family member and I was tempted to get rid of the mystery photo. The other day I looked again, more closely, noticing a certain detail for the first time. Half hidden against the sitter’s dark suit fabric, I saw the crook of a black walking stick and instantly understood who this was and the story that the picture told.

Belatedly I recognised my grandfather. He must have gained weight, less active after the loss of the leg. Perhaps someone had said “Get a dog Will!” encouraging him to do some companionable walking and regain fitness. The style of his clothes and the extra weight meant that the photo pre-dated his engagement portrait of 1921 which shows him more lean and trim. The name ‘USA Studio’ printed on the photo’s reverse triggered a 60 second internet search which revealed that between 1914 and 1919 this photography firm had a branch in Powis Street, Woolwich - just around the corner from the public baths where my grandfather worked as a baths attendant from 1920 until the early 1950s.

Looking at the picture, I remembered my mother repeating the story of how, on his return from France, William began to drink excessively and bet far too much on the horses. Perhaps he was catching up on youthful hedonism deferred by the war, but then again he might have been angrily confused and compensating, perhaps on the downward path from self-distraction to self-destruction. But the man in the photo doesn’t look like someone on the brink of losing self-control. His earnest, slightly apprehensive expression, his smart appearance, and the very decision to pay to have this formal portrait taken all seem more like the signs of someone who has found a good reason to refashion and reorient himself. He has the air of a person fully aware of having reached a turning point, and means the portrait to stand as a positive life-landmark. It’s an image of a young man who has survived war’s loss, distress, confusion and sheer horror - someone confronting the difficult challenge of accomplishing a return to ‘normal’, whatever normal could be made to be by a badly shaken 19 year old in 1919. I know what catalysed this change: the completely extraordinary yet totally normal experience of falling in love and being loved in return.

How long might it have taken William to re-learn how to walk? How long to pluck up enough courage to ask Daisy the Red Cross volunteer to dance? And when they danced, how many times did his false foot tread on her toes? How often did she need to brace rather than embrace as his new wooden leg tipped him off balance while they waltzed and turned?

William and Daisy's engagement photograph.

I vividly remember the lop-sided dancing he did with me not long after I had learned to walk. Waltzing, with my toddler-sized feet firmly planted on top of his, I could feel the difference, decades after the war, the energy and verve in his right foot and the wooden lack of it in his left. As we gathered speed, spinning around the sparse front-room furniture, the hinges of his leg creaked, and the dummy foot clumped across the bare lino. Perhaps some millennials, the children of parents disabled in 21st century wars, share a similar memory. Maybe they too remember feeling the sensations that I did while doing just the same kind of exuberantly defiant dancing, not to waltz tunes, but maybe to R and B or electro house.

The collection in the old suitcase yielded two more particularly telling photos of my grandfather, taken on a 1960s Italian holiday that he and my grandmother shared with her brother and his wife. My grandmother and her brother obviously took turns with the camera. Both the photos show William sunbathing in his swimming trunks. Beyond the family group, the beach is crowded with young, tanned, able-bodied men. One photo, taken by my grandmother, is carefully framed so that William’s stump is cropped out - an amputation of an amputation. In this picture a beach bag and towel are covering something pushed between the deck chairs. The other photo, taken by her brother, is more candid, or perhaps more careless, including not only the stump but also the things that the bag and towel were hiding - William’s wooden leg, its cumbersome harness, and his stump sock hung over the back of the deck chair.

When she stood up and took her turn with the camera, my grandmother would have instantly noticed the obviousness of the wooden leg. I don’t think that she framed the photo the way she did because she was ashamed of her husband’s disfigurement or his prosthetic, but she probably, even forty-plus years after the war, tended towards being highly protective of him. She must have anticipated how, back at home, when passing the holiday snaps around, her brother’s shot would needlessly reiterate and emphasise the difference between William’s body and everyone elses’. Perhaps the absent limb, the leg that was there but not there, and everything it recalled were just too painful for her to include, so starkly exposed, in her holiday photo.

Whenever the topic of the First World War was raised, my mother unfailingly claimed that her father refused to talk about it. It was a taboo subject. But I know of three brief exceptions. During my childhood, the word ‘war’ was often in the air. Curious, I decided to ask my grandfather outright “What is war?” I can still remember the awkward silence as he tried to summon an answer suitable for four-year-old ears. I persisted, bombarding him with irritating questions in the way that pre-school age children do. “What is it? Tell me.” Hesitantly he replied, “A lot of marching … a lot of hanging about … being outside all the time, living outside.” Wanting detail, I asked, “ Did you eat your food outside?” - “Yes”, he said tersely, before lapsing into an impenetrable silence.

The image that flashed into my mind was of hussars in quaint Regency style uniforms just like the ones I’d seen on Quality Street chocolate tins. I can still re-conjure my childish mental image of these improbably dandyish soldiers sitting about on the mown turf of a huge green field, eating neatly cut sandwiches. It is an innocent’s eye-view of war as a picnic - the polar opposite of the terrifying, bloody and chaotic reality that my grandfather was probably thinking of as he tried, or tried not, to answer me.

Another insight came uninvited, around the same time, when I saw my grandfather’s suppressed resentment burst like a shell in the room. Without warning his mood changed in a split second and he rounded on me bellowing, “You were born on a muck heap! Into shit!” He repeated the words more and more forcefully. Over his shoulder I caught sight of my grandmother watching through the doorway. Her expression indicated that I shouldn’t interrupt this outburst. I intuitively understood that the muck-heap he was shouting about was his metaphor for the war’s brutal destructiveness, all the unspoken damage it had left behind. I listened, not afraid or insulted because my mind was somehow making a direct connection between the furious swearing, the wooden leg, the stump and the part of the leg that wasn’t there.

I realise that I’m describing this incident from the entangled perspectives of both a four-year-old adult and an adult four-year-old: both views are skewed and incomplete. But in adult hindsight, I realise that my grandmother knew exactly what was going on. She must have heard such tirades before and knew that the usually concealed anger and frustration that drove it were part and parcel of their lives and always would be. She let the outburst go just so far, then she spoke very quietly, but very strongly, “Will. Enough. Will. That will do now.” And it was over.

The only time that my mother said she had heard her father mention the 1914 - 18 war was at the outbreak of World War Two, when he spoke with great bitterness and anger of what he had witnessed, telling not of the suffering of men, but of the suffering of horses. During a 1980s tape recording I made of my mother recounting her own childhood experience of the Blitz, she mentioned this once again. But why the horses? Although William was a cockney, London born and bred, my mother insisted that he was a country boy at heart. He loved to garden and my memories of his passion for blackberrying and blue-belling, his appreciation of birdsong and spring blossom are still crystal clear. This summer I learned from early census records that three generations, possibly more, of his family had worked with horses at the same farm in Loose, Kent. Why have I wanted to be around horses all my life? Inexplicably, some things just seem to stick. Every time I play the recording of my mother I am struck by the dramatic change of timbre in her voice as she repeats what her late father said about the horses’ screams. Her vocal chords begin to seize, strangling the words. I hear the echo of my grandfather choked with emotion, just as her nine-year-old self had unforgettably heard him. Somehow the power of his anguish still transmits through her voice and my recording of it, a whole century on.

My grandfather was an ordinary Tommy, not an officer, not mentioned in dispatches, not the recipient of any award for gallantry, just another one of the young men of his generation who did what they could, which turned out to be something completely remarkable. There is a sad irony about his ‘slight’ but life-changing injury. Having survived one of the last battles of the war, he made it back home, just days before the Armistice, but then became an amputee as a result of helpfulness rather than heroism. Was this outcome lucky or unlucky? He had come home alive but then paid a terrible forfeit. A cynic might say that by his own act of kindness he shot himself in his already shot foot. Despite this, his trait of enthusiastic helpfulness never left him. After snow he’d be the first one shovelling the pavements clear; he’d head out rain or shine on his pushbike to fetch my grandmother’s shopping; he supported younger World War Two amputees who came his way for advice via the British Limbless Ex-Service Mens’ Association (BLESMA). Virtually everyone he met succumbed to his infectious good humour.

Left: Fragment of a tablecloth embroidered by the wife of a BLESMA contact as a thankyou for William's support of her husband. Right: William with BLESMA friends.

Writing this piece has been slow work, interspersed with time spent trawling the internet for images of people and places whose names have cropped up. The value of this searching is that it has enabled me to see more explicit visual detail of William’s war experience than either my mother or grandmother ever could have. Via the internet, I’ve explored the hospital trains’ interiors and found photos of the American hospital’s operating theatre and the wards at Walden Place. Through watching archive film of squads of young amputees trying out their new prosthetics at Roehampton, I can understand something of the physical experience he underwent. The scores of photos that recorded the devastation inflicted on Bapaume have allowed me to see the town’s vistas of unmitigated ruin, rubble and wreckage, the dead and injured horses lying on its roads.

Detail of reverse of Pte. William Pearson's 1914-1918 War Medal.

Accessing that information required no more effort than the tapping of my fingertips on the keyboard. Finding it has made the reverse trajectory impossible: now I cannot un-know or erase this new-found knowledge of my grandfather’s experience any more than he could obliterate the memories of what he saw first-hand. Documents, pictures, objects, and a few indisputable facts flesh out his story, but it also contains many blanks, many unanswerable questions. To ignore or write out the awkward silences, the rare eruptions of resentful rage, would amount to a kind of censorship, a denial of the sheer effort that First World War veterans expended in managing often unbearable psychological wounding. Well before their 20th birthdays, both my grandparents experienced irreparable loss. When my grandmother first met William, she must still have been grieving for her first fiancé, a soldier who did not return from the battlefield. Losing a limb and losing a first love might, superficially, seem like very different things. But, ultimately those losses and their devastating effects proved to be similar enough to hold my grandparents in mutually empathetic and supportive love for the rest of their lives.

On Armistice day I didn’t attend a wreath-laying service, or hear a gun-salute or the tolling of bells. These public gestures of reverencing the dead are important. But the thing that I have tried to commemorate and emphasise is some of what went on in private, day to day, in the everyday domestic sphere during the decades following the war. What I have written acknowledges the valour that survivors and their closest relatives had to find within themselves for a lifetime, the courage to get on and live.

How did I mark the Centenary’s moment? Given that the war was fought, as the Victory Medal’s inscription says, ‘for civilisation’, it seemed only right to take time to immerse myself in the small but vital pleasures that civilisation, peace itself, not only allows but actually consists of. I walked the dog, spent time with the horse, savoured the autumn colours, listened to the wrens singing in the hedge. I polished my grandfather’s medals, reflected on what they cost him. I thought a little about their worth too (no more than a tenner on eBay) and then spent longer considering their immeasurable value. I don’t know if William would approve of any of this: would he interpret what I have written, my candour, as an intrusion into the silence he wanted to maintain? Would he, and other self-silenced men of his generation, read my account as a disobedient betrayal of their determination not to put war and all its wounds into words? - words that like the lost leg were always there, but which were constantly resisted, unspoken, never heard, and so not actually there. Perhaps.

What I am certain of is the amazement and pride William would have felt if he could see this autumn’s commemorative spectacle - the vast efflorescence of poppies, the Tommy silhouettes, the flickering nocturnal flames and shadows at the Tower, and the 72,000 tiny shrouded figures at the Olympic Park in Stratford, just down the road from where he volunteered. I am so glad to be here to tell all this, glad too that William’s great grand-daughter, Anna, will see something of her great-grandparents’ lives, their losses and loves written down, brought into the light, at last, up on her screen.

888,246 ceramic poppies: one for each serviceman or woman who did not return.

(Photo: James White. 10.45am 11.11.2014.)

Kim Crowder, November 2018.

The background of this page is a made from part of an image of one of William Pearson's stump socks, now preserved with other war memorabilia that once belonged to him.