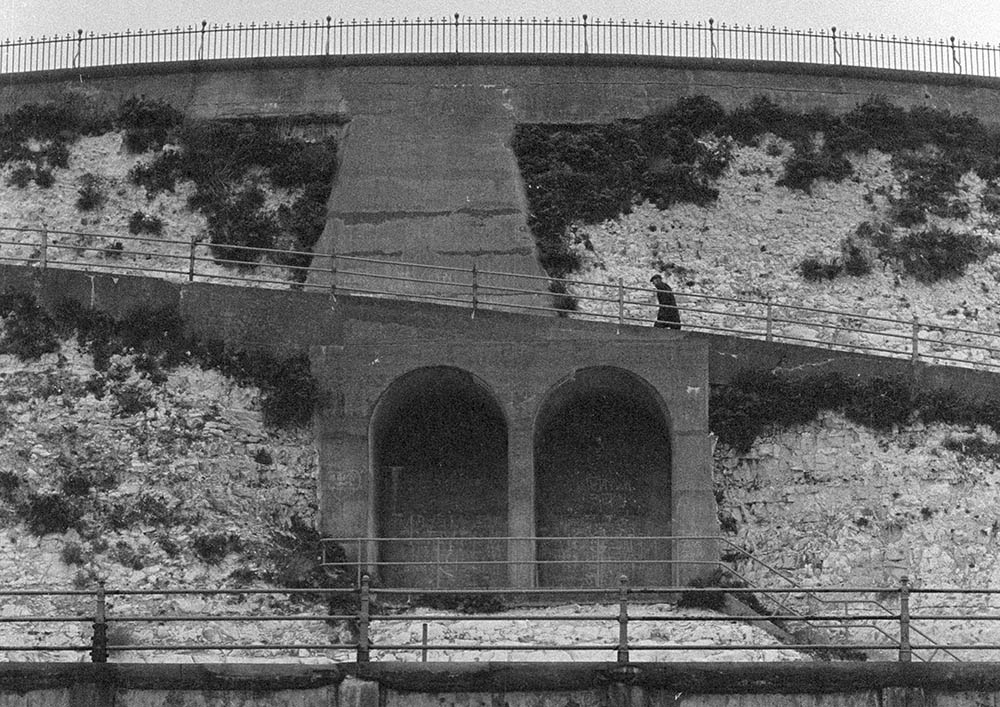

The West Cliff Promenade, Ramsgate, 1974.

The West Cliff Promenade, Ramsgate, 1974.

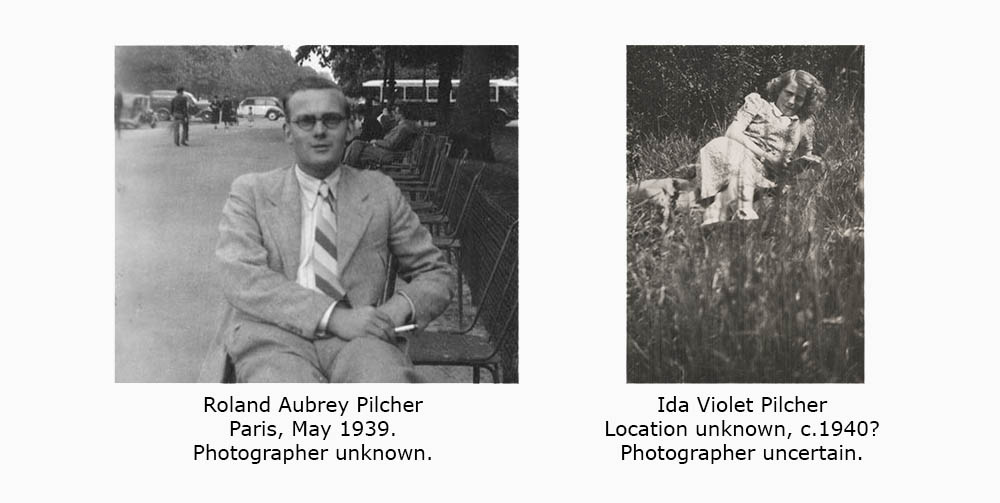

Now, one November afternoon shortly before my mother died, I visited her younger brother, my uncle Roland. He gave me a small, leather bound, photo-album containing family pictures that he had taken from the time of his childhood, in the 1920s, up until 1964 when he was forty five. The ordering of the photographs is not chronological, the last page is a picture from around 1930 and the 1964 image is stuck into the middle of the book. In every picture, except one, the subjects pose for the camera. The one exception is an image of my mother.

Now, one November afternoon shortly before my mother died, I visited her younger brother, my uncle Roland. He gave me a small, leather bound, photo-album containing family pictures that he had taken from the time of his childhood, in the 1920s, up until 1964 when he was forty five. The ordering of the photographs is not chronological, the last page is a picture from around 1930 and the 1964 image is stuck into the middle of the book. In every picture, except one, the subjects pose for the camera. The one exception is an image of my mother.

She is lying in long grass, looking up from a book. The camera angle is very low: she is seen through a blur of grass, one blade is so completely out of focus that it does no more than darken the right side of her face. At first, I thought she was in her early twenties and I imagined my uncle Roland, at the age of ten or eleven stalking her, and causing some irritation, with his Box Brownie. But, perhaps, she is older. Her dress might be from the late thirties or even later. It may be 1940 or '41, and her expression might not be irritation at a pestering younger brother but wartime apprehension. I can imagine Roland, on leave from army training, slithering through the grass to snap his sister in a playful analogy of what he might soon be required to do with a gun. The photograph could not have been taken between 1942 and 1945 because Uncle Roland had been sent to the Far East, where, from the 8th of March 1942 until the 2nd of September 1945, he was a prisoner, spending most of that time in a camp at Motoyama, in Japan, that at the end was called Hiroshima 8B. Perhaps it is 1946 and that troubled look has been caught before she could hide it from a brother who had been “missing presumed dead” but had returned, emaciated, traumatised by years of imprisonment and forced labour in a coal mine and having witnessed, as a distant earthquake and a rising, malignant, cloud formation, one of the most catastrophic events in human history. Perhaps he was too weak, had lost the will, to lift the camera much above the long grass.

I took the little album to the nursing home where my mother spent her last days. One of the staff there said “Ida, you look like a film star”. To me, through the scratched and faded surface of the print, she looks like an intelligent and capable woman, a worker on her day off, who seems to be asking “What is going to happen?” Or perhaps “What will be required of me?” I notice her white leather shoes, her hair, the set of her body, the carefully chosen, or perhaps home-made dress, a rather beautiful wristwatch, but I feel a distance. To be moved by any of these things seems like a presumptuous imposition. I can't subvert by my thoughts, my emotion, my speculative interpretation of the realities that form this picture: the coincidence of light, optics, chemistry, time, and the decisions of its makers (which includes the camera and film makers, the processors and printers, as well as the photographer and apparent subject). It is a document that has a place, however ambiguous, in a personal, social, historical and a political context, but any understanding of it is only possible by remaking and representing it to the mind, by telling a story about it, as I have done here. Any truth it holds needs information, facts, from before and after it was made. What really moves me in this image is not any private wound or prick of meaning; its real significance for me, what holds me to it, is a shared uncertainty.

The physical form of a photographic image, whether it is coloured light on a screen, ink on paper or silver salts in a gelatin emulsion, is what creates the illusion of the object, or communicates the idea, or emotion, of the picture. For the painted object, the oil on canvas or watercolour on paper, there are a myriad of processes and techniques available: from drawing and design to the physicality of glaze and scumble, impasto, scraffito, stipple, little brush strokes, bold brushing, and the millions of combinations of chroma, lightness and hue available in paint. The photographic object is made through a corresponding array: lens perspective, camera position and angle, contrast and brightness, grain and focus, the range of manipulable colour and tonal possibilities that photographic processes produce in response to particular qualities of light. The physical object of a photograph is constructed of these elements. It is an account, not an emanation, although, in our pleasure in the illusion, we may suspend our inherent understanding that there is no direct link with reality.

There may be no direct link between vision and reality either. In both our eyes and the camera, the lens focuses an image onto a surface: this image has a direct, physical link to the light reflected by objects in the world. But in vision and photography what happens next is that this image is processed. It is turned into something other. The images of both photography and perception are analogs. It may be that part of the pleasure to be derived from looking at pictures comes from a recognition of this disjuncture. Perhaps the burgeoning of photography, in both production and dissemination, made possible by 'phones and tablets is changing human understanding of photographic images to things that are made, rather than as magical emanations formed by a process of nature. Today, a five year old with her first smart phone will soon become adept at distinguishing the photographic signifier from the referent: she will make cool photos, not record “what has been”. She will delight in the magic of colour and light on screen and begin, at least, to apprehend the possibility of meanings in the coincidence of colour and form, and the light that always comes out of darkness.

For me, there exists an image as real and present as any photograph. A few minutes after I had seen my mother for the last time, I stood on the cliff top at Ramsgate, the West Cliff Promenade, beside the lift. It was a cold November night. Below me I could see concrete breakwaters and to my left the lights and buildings of the harbour. But that was all. When I looked beyond there was a void reaching up from the concrete below, filling my vision. I knew, I know, that there would have been the lights of ships, the glow of the towns of Deal and Sandwich to my right, a change between sea and sky at the horizon (perhaps the dim glow of the French coast at Calais that can sometimes be seen). Behind me the sheer flint walls of Pugin's Grange foamed in the darkness. But these things were below the threshold. In front of me, for a few moments, there was only a dense blackness. I could see nothing. In my mind, pictures of my life in this place vanished before they could appear. The album almost opened and then its pages flickered shut. Images were exposed, then wafered to nothing, they floated and then vanished as if made from some fugitive code. Something skeined, giddying, around the edges of my perception. A sickening iridescence on the surface of a bubble that enclosed nothing but an absolute, zone zero, d-max, #000000, darkness.

The West Cliff Promenade, Ramsgate, 1974.

An earlier version of the above text was published in 2005 by Norwich School of Art in Photographic Studies One, the booklet accompanying the final show of the MA Photography course. At the time Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes, which blends highly personal and emotional reflections with theorising on the nature of photography, was effectively required reading on photography courses, probably on most art courses, and its ideas were often quoted as if they were Holy Writ. My text, in its subject matter and its style, was intended to both allude to and suggest a questioning of Barthes. In the book, Barthes reflects on a photograph of his mother that he came across shortly after her death but he does not reproduce it: I see no reason for me to be so coy. Camera Lucida is an intensely thought provoking book, but I felt that Barthes' intention to find the essence of photography for himself (as a person who, he claimed, was not even an amateur photographer but actually incapable of making a photograph) was potentially a source of misleading, and mistaken, ideas for practitioners, for makers.

An earlier version of the above text was published in 2005 by Norwich School of Art in Photographic Studies One, the booklet accompanying the final show of the MA Photography course. At the time Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes, which blends highly personal and emotional reflections with theorising on the nature of photography, was effectively required reading on photography courses, probably on most art courses, and its ideas were often quoted as if they were Holy Writ. My text, in its subject matter and its style, was intended to both allude to and suggest a questioning of Barthes. In the book, Barthes reflects on a photograph of his mother that he came across shortly after her death but he does not reproduce it: I see no reason for me to be so coy. Camera Lucida is an intensely thought provoking book, but I felt that Barthes' intention to find the essence of photography for himself (as a person who, he claimed, was not even an amateur photographer but actually incapable of making a photograph) was potentially a source of misleading, and mistaken, ideas for practitioners, for makers.

The West Cliff Promenade, Ramsgate, 1974.

Details of Roland Pilcher's years in Japan, and images of his Japanese prison record card, can be found at http://www.roll-of-honour.org.uk/p/html/pilcher-roland-aubrey.htm

After being ordered to surrender, Roland was transferred from Java to Japan on two ships. First, the Yoshida Maru to Singapore and then the Singapore Maru to Japan. When he visited us in Ramsgate, in the early 1960s, he was reluctant to go too close to the sea, especially to look down on it from the cliff top. We would walk and sit in the Rose Garden instead, which was almost torture for me at the age of six or seven. My brother and I began to tease him but were stopped by my mother who took us aside and told us that something horrible had happened to him in the war and we must be kind, like he was, and try to understand. I often wondered what it might have been that had made my favourite uncle so reluctant to enjoy the excitement of the cliff top and the beauty and fun of the sea. Now, having read the account by A. G. James of the “Hell Ships”, I can begin to imagine (See: http://www.far-eastern-heroes.org.uk/hell_ship/html/hell_ship.htm).

Details of Roland Pilcher's years in Japan, and images of his Japanese prison record card, can be found at http://www.roll-of-honour.org.uk/p/html/pilcher-roland-aubrey.htm

After being ordered to surrender, Roland was transferred from Java to Japan on two ships. First, the Yoshida Maru to Singapore and then the Singapore Maru to Japan. When he visited us in Ramsgate, in the early 1960s, he was reluctant to go too close to the sea, especially to look down on it from the cliff top. We would walk and sit in the Rose Garden instead, which was almost torture for me at the age of six or seven. My brother and I began to tease him but were stopped by my mother who took us aside and told us that something horrible had happened to him in the war and we must be kind, like he was, and try to understand. I often wondered what it might have been that had made my favourite uncle so reluctant to enjoy the excitement of the cliff top and the beauty and fun of the sea. Now, having read the account by A. G. James of the “Hell Ships”, I can begin to imagine (See: http://www.far-eastern-heroes.org.uk/hell_ship/html/hell_ship.htm).

The writer and actor Ken Attiwill, was in the same prison camp as Roland Pilcher and wrote an account of his experiences (Attiwill, K. 1957. The Rising Sunset, Robert Hale, London). In my 1958 paperback edition Corporal Pilcher is mentioned on pages 153 and 165 and an account of what the prisoners in Hiroshima 8B saw on August 9th, 1945 at 11.01am is on page 188. When I visited him in 1996 Roland began to speak of his wartime experiences. I asked him if the prisoners were aware of the nuclear bomb, he said something like “We saw it, strange clouds a long way off, and we felt it. A day or two later we woke up and all the guards had gone”. I did not ask if it was Hiroshima or Nagasaki that he had seen and felt, but my memory of his account corroborates Attiwill's description which only refers to Nagasaki. Hiroshima 8B camp was, in a straight line, about 75 miles from Hiroshima and 100 miles from Nagasaki. They almost got a much closer look: the primary target on the 9th of August was Kokura, about 20 miles away across the Seto Inland Sea, but clouds and smoke from American fire bombing the previous day obscured the target and the planes diverted.

The West Cliff Promenade, Ramsgate, 1974.

The West Cliff area of Ramsgate was developed in the 1920s and early '30s. My Family moved to Ramsgate in 1959 and we soon began to be visited by aunties, uncles and cousins wanting a day, or longer, by the seaside. In the early 1960s Ramsgate was still a busy seaside holiday town with a large and sprawling beach and funfair, Pleasurama, to the east of the Royal Harbour. On summer evenings the fragrances of sea and salt, vinegar, chips, beer and candyfloss were always in the air. But the West Cliff, with only one comparatively sedate cafe on the cliff top, was where the local people went. We spent long summer days swimming, building sand castles and exploring rock pools, seeing the annual carnival procession loop around the Royal Esplanade in August, playing golf on the putting green, looking down from the cliff top at the motor cycle time trials on the long Undercliff Drive (with a wonderful smell of burning oil and fuel wafting up and a distorting Tannoy amplifying roaring engines and a frantic commentary), winding the hand powered paddle boats in the lido where the band stand had once been, watching the smart older ladies and gentlemen in panama hats playing bowls. My memory of this time is of a sunny picture full of life. A history of the West Cliff area of Ramsgate can be found at http://ramsgate-society.org.uk/ramsgatematters/index.php/local-news/local-history/2-west-cliff-225-years

The West Cliff area of Ramsgate was developed in the 1920s and early '30s. My Family moved to Ramsgate in 1959 and we soon began to be visited by aunties, uncles and cousins wanting a day, or longer, by the seaside. In the early 1960s Ramsgate was still a busy seaside holiday town with a large and sprawling beach and funfair, Pleasurama, to the east of the Royal Harbour. On summer evenings the fragrances of sea and salt, vinegar, chips, beer and candyfloss were always in the air. But the West Cliff, with only one comparatively sedate cafe on the cliff top, was where the local people went. We spent long summer days swimming, building sand castles and exploring rock pools, seeing the annual carnival procession loop around the Royal Esplanade in August, playing golf on the putting green, looking down from the cliff top at the motor cycle time trials on the long Undercliff Drive (with a wonderful smell of burning oil and fuel wafting up and a distorting Tannoy amplifying roaring engines and a frantic commentary), winding the hand powered paddle boats in the lido where the band stand had once been, watching the smart older ladies and gentlemen in panama hats playing bowls. My memory of this time is of a sunny picture full of life. A history of the West Cliff area of Ramsgate can be found at http://ramsgate-society.org.uk/ramsgatematters/index.php/local-news/local-history/2-west-cliff-225-years

The West Cliff Promenade, Ramsgate, 1974.

Most of the photographs that form the West Cliff pictures in my Edge of a Sea photographs were exposed during the winter of 1973/74. By this time the decline of English resorts was well advanced and the luminous playground of my youth was decaying. In the first three months of 1974, when Britain was on a three day week, with frequent power cuts, television closed down at 10.30pm and the weather was mild but dark and damp, I took over two hundred photographs on the Promenade and Undercliff. I was in my second year at art school and, I think, I recognised this place as being on the edge – the edge of time, of politics, of nature - but at the same time I saw it as a cultural and historic space and an artefact of a transitional civilisation. At art school we learned about land art and the work of Robert Smithson and Christo. To me the Spiral Jetty and Wrapped Coast seemed to have a profound antecedent in the West Cliff Promenade. But this place seemed more like the great English Cathedrals than any iteration of modernist art. Made to enthral through generations, a place to breathe, socialise and contemplate, it ran for a mile from Court Stairs Park to just above the harbour. Balanced on great concrete arches set into the chalk cliffs at the edge of the sea, on the stubby finger of Kent that points to the continent of Europe, it still seemed to project a relaxed and powerful confidence. Somehow through the dark of a troubled winter, despite its own decay and that of the culture that had made it, the grandeur of the West Cliff Promenade held. It was, like memory, precarious but quietly, intensely, crucial.

Most of the photographs that form the West Cliff pictures in my Edge of a Sea photographs were exposed during the winter of 1973/74. By this time the decline of English resorts was well advanced and the luminous playground of my youth was decaying. In the first three months of 1974, when Britain was on a three day week, with frequent power cuts, television closed down at 10.30pm and the weather was mild but dark and damp, I took over two hundred photographs on the Promenade and Undercliff. I was in my second year at art school and, I think, I recognised this place as being on the edge – the edge of time, of politics, of nature - but at the same time I saw it as a cultural and historic space and an artefact of a transitional civilisation. At art school we learned about land art and the work of Robert Smithson and Christo. To me the Spiral Jetty and Wrapped Coast seemed to have a profound antecedent in the West Cliff Promenade. But this place seemed more like the great English Cathedrals than any iteration of modernist art. Made to enthral through generations, a place to breathe, socialise and contemplate, it ran for a mile from Court Stairs Park to just above the harbour. Balanced on great concrete arches set into the chalk cliffs at the edge of the sea, on the stubby finger of Kent that points to the continent of Europe, it still seemed to project a relaxed and powerful confidence. Somehow through the dark of a troubled winter, despite its own decay and that of the culture that had made it, the grandeur of the West Cliff Promenade held. It was, like memory, precarious but quietly, intensely, crucial.

The Western Undercliff, Ramsgate, 1974.

The Western Undercliff, Ramsgate, 1974.

The Western Undercliff, Ramsgate, 1974.

Images and texts by P.F.WHITE (Peter Frankland White). ACTIVE: 196Os to the present. LOCATION: Europe (United Kingdom). SUBJECTS: vision, perception, location, time(s), class, power, rhilopia. STYLE: exploratory, aggregative, aleatory, attentive, punctum averse.

All material (except where otherwise acknowledged) is © Peter Frankland White, , and may not be reproduced in any form without written consent. See: Notes on Rights, Ethics, Privacy and Consent. Page design by Allpicture.